Bringing new worlds to life doesn’t end with bleeding-edge software – it’s also a battle with the laws of physics. Project North Star is a compelling glimpse into the future of AR interaction and an exciting engineering challenge, with wide-FOV displays and optics that demanded a whole new calibration and distortion system.

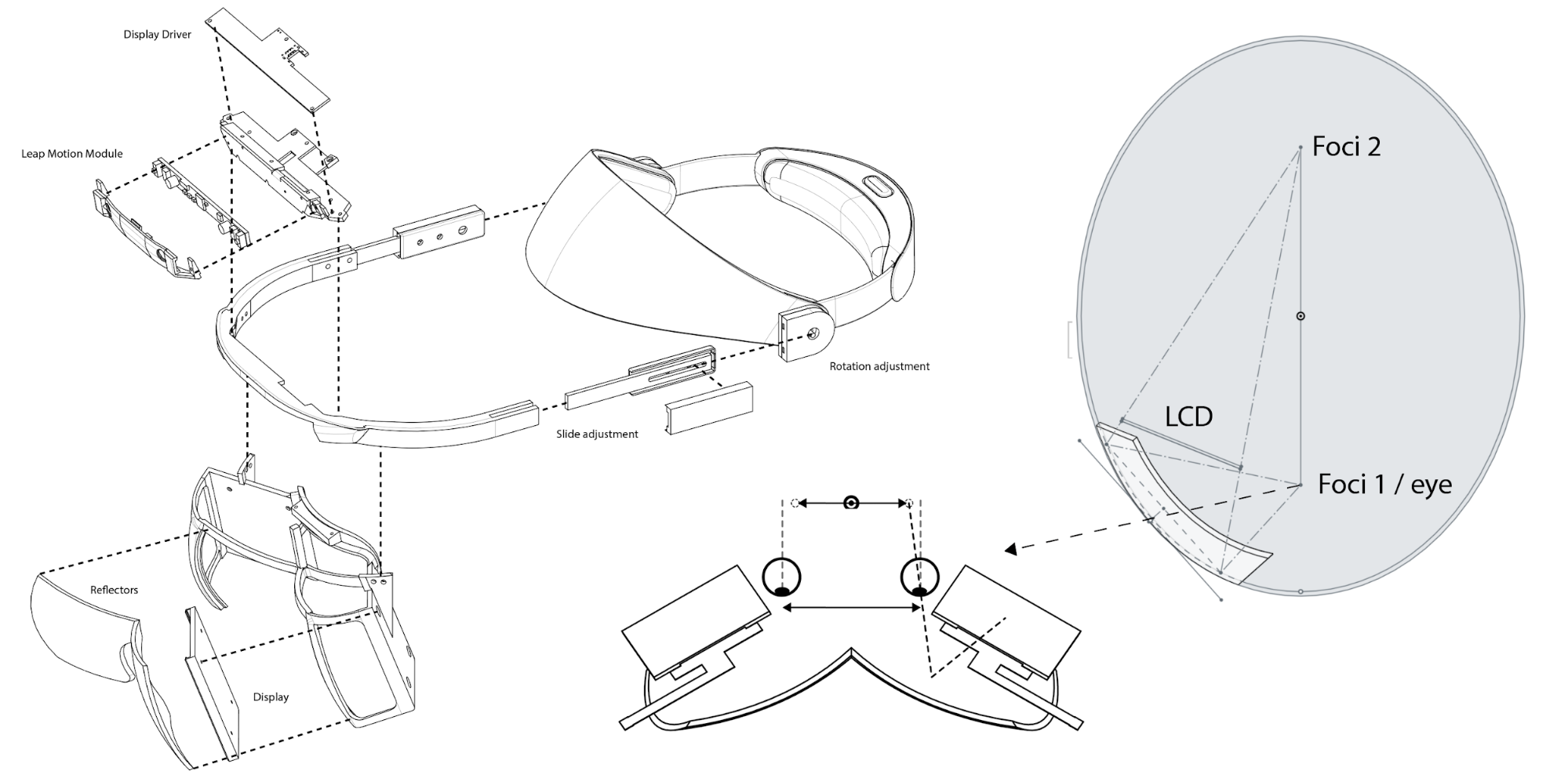

Just as a quick primer: the North Star headset has two screens on either side. These screens face towards the reflectors in front of the wearer. As their name suggests, the reflectors reflect the light coming from the screens, and into the wearer’s eyes.

As you can imagine, this requires a high degree of calibration and alignment, especially in AR. In VR, our brains often gloss over mismatches in time and space, because we have nothing to visually compare them to. In AR, we can see the virtual and real worlds simultaneously – an unforgiving standard that requires a high degree of accuracy.

North Star sets an even higher bar for accuracy and performance, since it must be maintained across a much wider field of view than any previous AR headset. To top it all off, North Star’s optics create a stereo-divergent off-axis distortion that can’t be modelled accurately with conventional radial polynomials.

North Star sets a high bar for accuracy and performance, since it must be maintained across a much wider field of view than any previous augmented reality headset. Click To TweetHow can we achieve this high standard? Only with a distortion model that faithfully represents the physical geometry of the optical system. The best way to model any optical system is by raytracing – the process of tracing the path rays of light travel from the light source, through the optical system, to the eye.[1] Raytracing makes it possible to simulate where a given ray of light entering the eye came from on the display, so we can precisely map the distortion between the eye and the screen.[2]

But wait! This only works properly if we know the geometry of the optical system. This is hard with modern small-scale prototyping techniques, which achieve price effectiveness at the cost of poor mechanical tolerancing (relative to the requirements of near-eye optical systems). In developing North Star, we needed a way to measure these mechanical deviations to create a valid distortion mapping.

One of the best ways to understand an optical system is… looking through it!. By comparing what we see against some real-world reference, we can measure the aggregate deviation of the components in the system. A special class of algorithms called “numerical optimizers” lets us solve for the configuration of optical components that minimizes the distortion mismatch between the real-world reference and the virtual image.

Leap Motion North Star calibration combines a foundational principle of Newtonian optics with virtual jiggling. Click To TweetFor convenience, we found it was possible to construct our calibration system entirely in the same base 3D environment that handles optical raytracing and 3D rendering. We begin by setting up one of our newer 64mm camera modules inside the headset and pointing it towards a large flat-screen LCD monitor. A pattern on the monitor lets us to triangulate its position and orientation relative to the headset rig.

With this, we can render an inverted virtual monitor on the headset in the same position as the real monitor in the world. If the two versions of the monitor matched up perfectly, they would additively cancel out to uniform white.[3] (Thanks Newton!) The module can now measure this “deviation from perfect white” as the distortion error caused by the mechanical discrepancy between the physical optical system and the CAD model the raytracer is based on.

This “one-shot” photometric cost metric allows for a speedy enough evaluation to run a gradientless simplex Nelder-Mead optimizer in-the-loop. (Basically, it jiggles the optical elements around until the deviation is below an acceptable level.) While this might sound inefficient, in practice it lets us converge on the correct configuration with a very high degree of precision.[4]

This might be where the story ends – but there are two subtle ways that the optimizer can reach a wrong conclusion. The first kind of local minima rarely arises in practice.[5] The more devious kind comes from the fact that there are multiple optical configurations that can yield the same geometric distortion when viewed from a single perspective. The equally devious solution is to film each eye’s optics from two cameras simultaneously. This lets us solve for a truly accurate optical system for each headset that can be raytraced from any perspective.

In static optical systems, it usually isn’t worth going through the trouble of determining per-headset optical models for distortion correction. However, near-eye displays are anything but static. Eye positions change for lots of reasons – different people’s interpupillary distances (IPDs), headset ergonomics, even the gradual shift of the headset on the head over a session. Any one of these factors alone can hamper the illusion of augmented reality.

Fortunately, by combining the raytracing model with eye tracking, we can compensate for these inconsistencies in real-time for free![6] We’ll cover the North Star eye tracking experiments in a future blog post.