When we embarked on this journey, there were many things we didn’t know.

What does hand tracking need to be like for an augmented reality headset? How fast does it need to be; do we need a hundred frames per second tracking or a thousand frames per second?

How does the field of view impact the interaction paradigm? How do we interact with things when we only have the central field, or a wider field? At what point does physical interaction become commonplace? How does the comfort of the interactions themselves relate to the headset’s field of view?

What are the artistic aspects that need to be considered in augmented interfaces? Can we simply throw things on as-is and make our hands occlude things and call it a day? Or are there fundamentally different styles of everything that suddenly come out when we have a display that can only ‘add light’ but not subtract it?

These are all huge things to know. They impact the roadmaps for our technology, our interaction design, the kinds of products people make, what consumers want or expect. So it was incredibly important for us to figure out a path that let us address as many of these things as possible.

To this end, we wanted to create something with the highest possible technical specifications, and then work our way down until we had something that struck a balance between performance and form-factor.

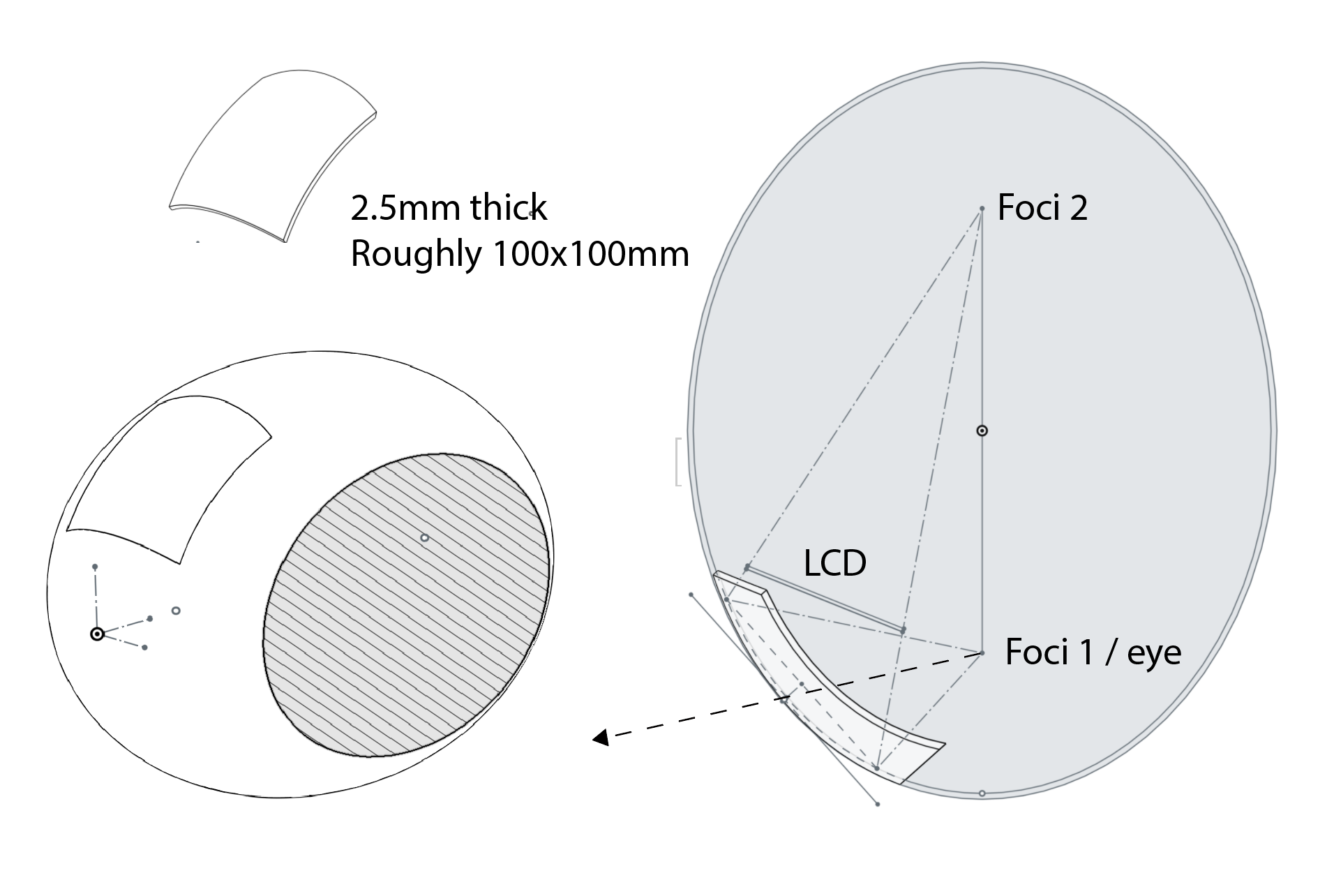

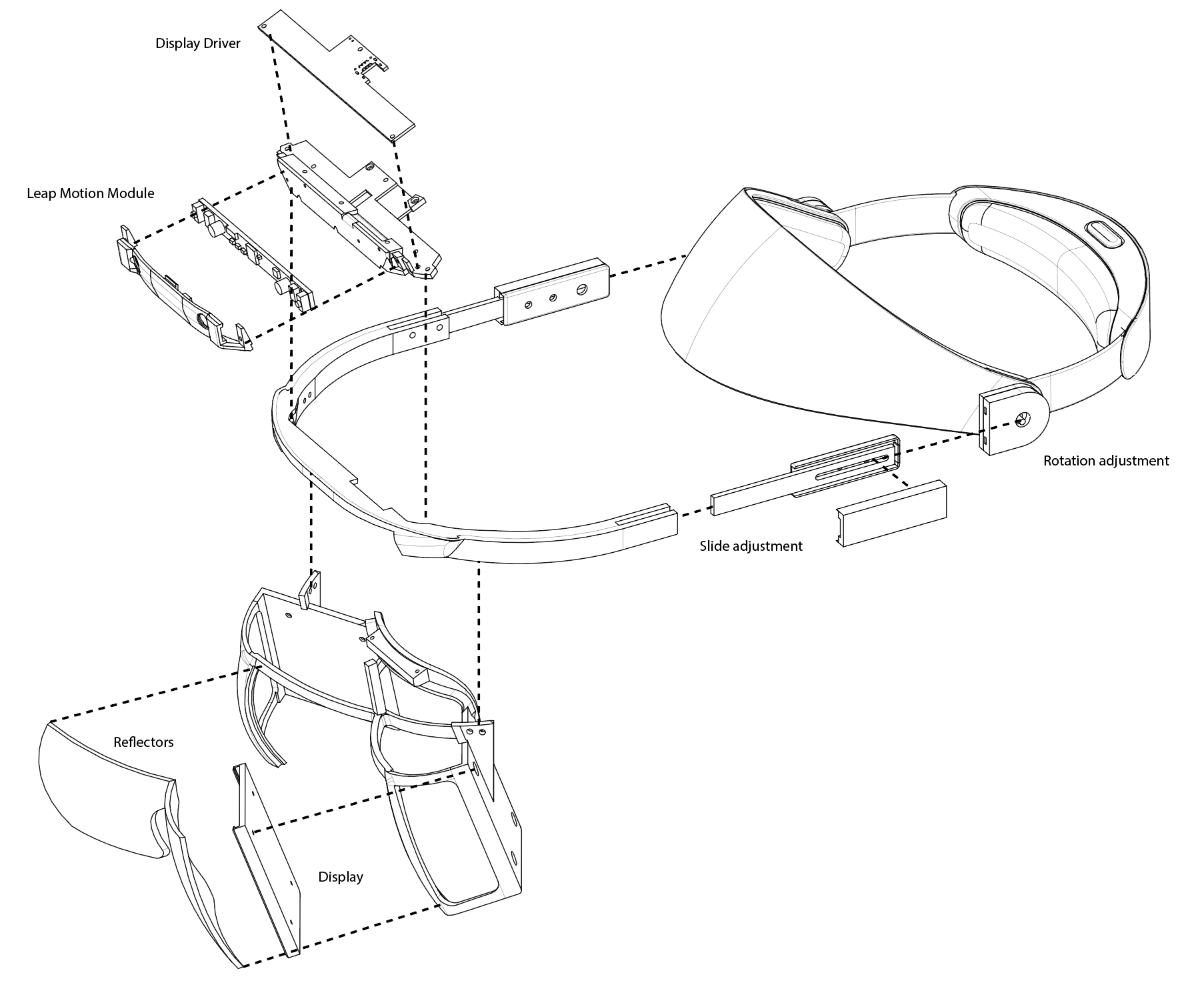

All of these systems function using ‘ellipsoidal reflectors’, or sections of curved mirror which are cut from a larger ellipsoid. Due to the unique geometry of ellipses, if a display is put on one side of the curve and the user’s eye on the other, then the resulting image will be big, clear, and in focus.

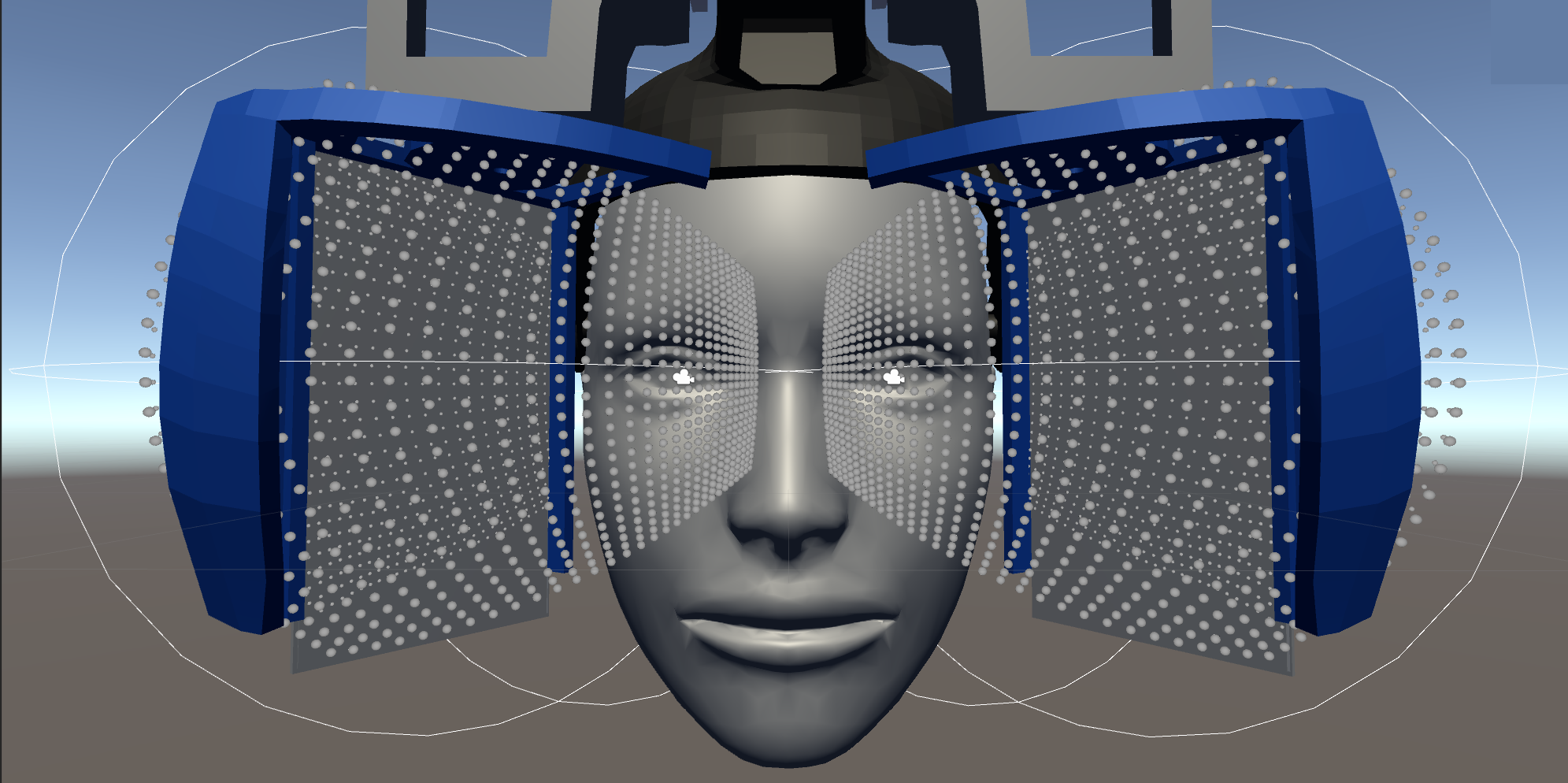

We started by constructing a computer model of the system to get a sense of the design space. We decided to build it around 5.5-inch smartphone displays with the largest reflector area possible.

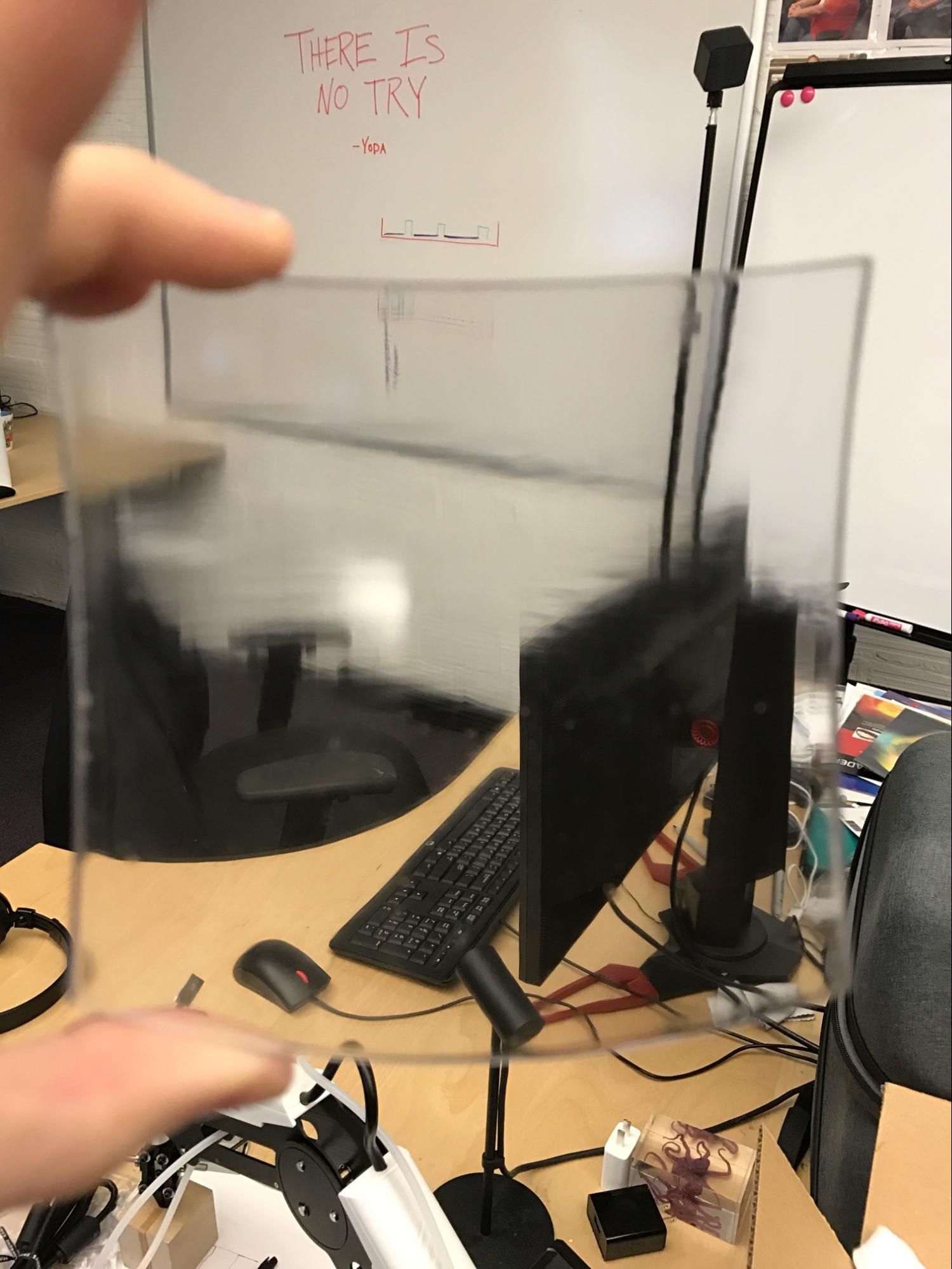

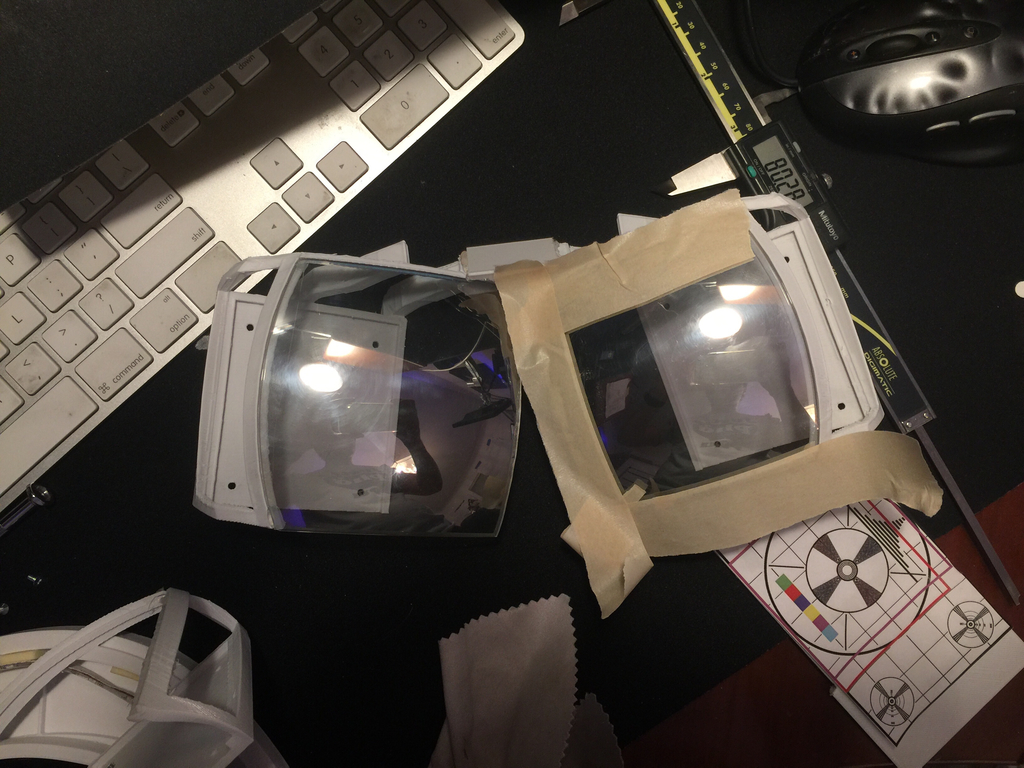

Next, we 3D-printed a few prototype reflectors (using the VeroClear resin with a Stratasys Objet 3D printer), which were hazy but let us prove the concept: We knew we were on the right path.

The next step was to carve a pair of prototype reflectors from a solid block of optical-grade acrylic. The reflectors needed to possess a smooth, precise surface (accurate to a fraction of a wavelength of light) in order to reflect a clear image while also being optically transparent. Manufacturing optics with this level of precision requires expensive tooling, so we “turned” to diamond turning (the process of rotating an optic on a vibration-controlled lathe with a diamond-tipped tool-piece).

Soon we had our first reflectors, which we coated with a thin layer of silver (like a mirror) to make them reflect 50% of light and transmit 50% of light. Due to the logarithmic sensitivity of the eye, this feels very clear while still reflecting significant light from the displays.

We mounted these reflectors inside of a mechanical rig that let us experiment with different angles. Behind each reflector is a 5.5″ LCD panel, with ribbon cables connecting to display drivers on the top.

While it might seem a bit funny, it was perhaps the widest field of view, and the highest-resolution AR system ever made. Each eye saw digital content approximately 105° high by 75° wide with a 60% stereo overlap, for a combined field of view of 105° by 105° with 1440×2560 resolution per eye.

The vertical field of view struck us most of all; we could now look down with our eyes, put our hands at our chests and still see augmented information overlaid on top of our hands. This was not the minimal functionality required for a compelling experience, this was luxury.

This system allowed us to experiment with a variety of different fields of view, where we could artificially crop things down until we found a reasonable tradeoff between form factor and experience.

We found this sweet spot around 95° x 70° with a 20 degree vertical (downwards) tilt and a 65% stereo overlap. Once we had this selected, we could cut the reflectors to a smaller size. We found the optimal minimization amount empirically by wearing the headset and marking the reflected displays’ edges on the reflectors with tape. From here, it was a simple matter of grinding them down to their optimal size.

The second thing that struck us during this testing process was just how important the framerate of the system is. The original headset boasted an unfortunate 50 fps, creating a constant and impossible to ignore slosh in the experience. With the smaller reflectors, we could move to smaller display panels with higher refresh rates.

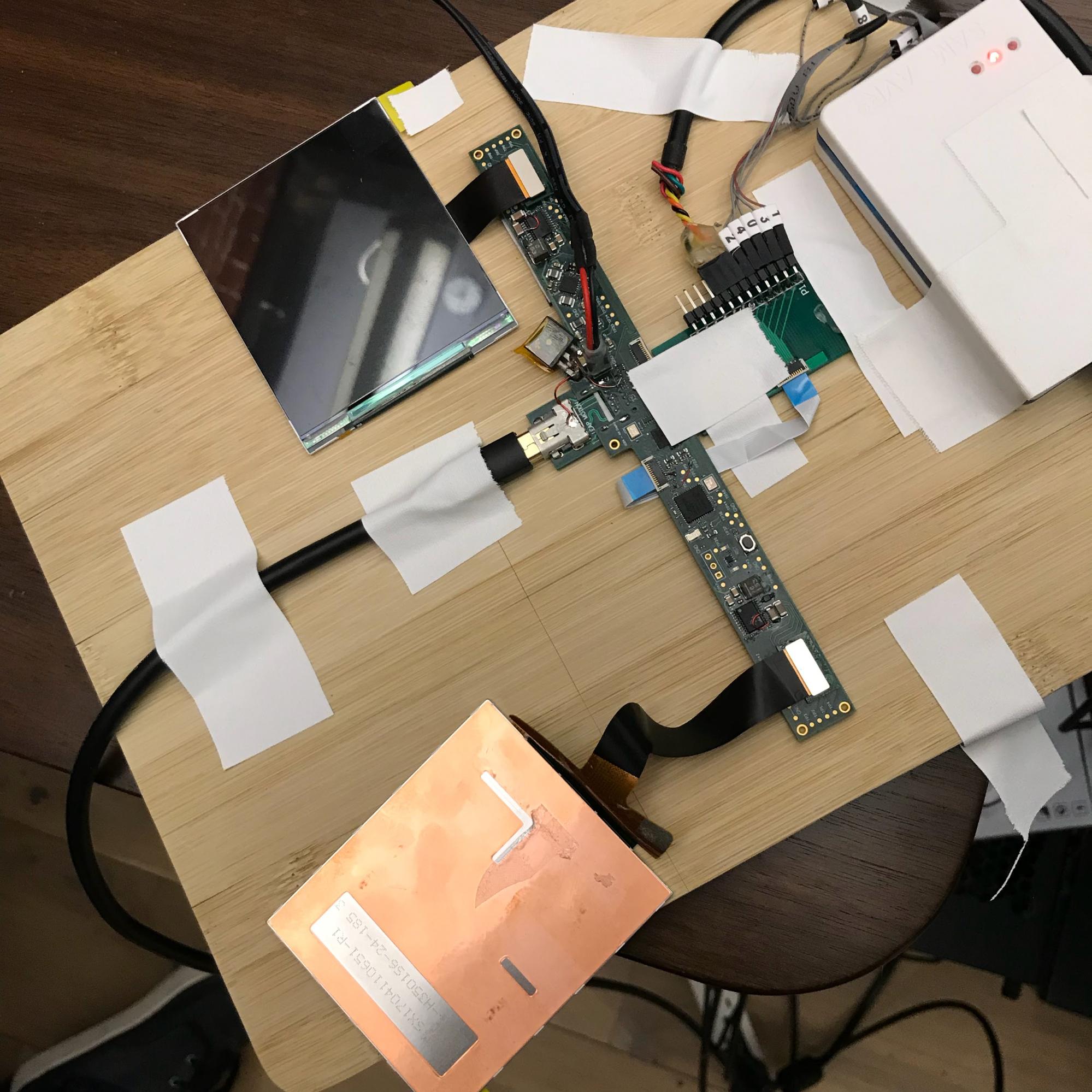

At this point, we needed to make our own LCD display system (nothing off the shelf goes fast enough). We settled on a system architecture that combines an Analogix display driver with two fast-switching 3.5″ LCDs from BOE Displays.

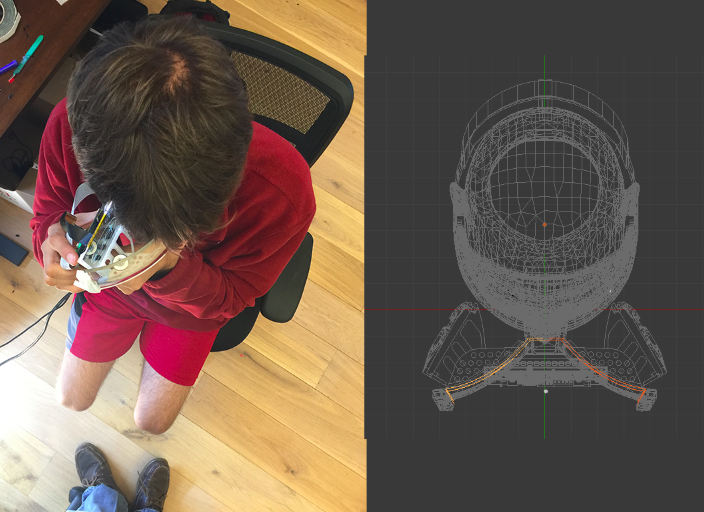

Put together, we now had a system that felt remarkably smaller:

The reduced weight and size feel exponential. Every time we cut away one centimeter, it felt like we cut off three.

We ended up with something roughly the size of a virtual reality headset. In whole it has fewer parts and preserves most of our natural field of view. The combination of the open air design and the transparency generally made it feel immediately more comfortable than virtual reality systems (which was actually a bit surprising to everyone who used it).

We mounted everything on the bottom of a pivoting ‘halo’ that let you flip it up like a visor and move it in and out from your face (depending on whether you had glasses).

Sliding the reflectors slightly out from your face gave room for a wearable camera, which we threw together created from a disassembled Logitech (wide FoV) webcam.

All of the videos you’ve seen were recorded with a combination of these glasses and the headset above.

Last we want to do one more revision on the design to have room for enclosed sensors and electronics, better cable management, cleaner ergonomics and better curves (why not?) and support for off the shelf head-gear mounting systems. This is the design we are planning to open source next week.

There remain many details we feel that would be important to further progressions of this headset. Some of which are:

- Inward-facing embedded cameras for automatic and precise alignment of the augmented image with the user’s eyes as well as eye and face tracking.

- Head mounted ambient light sensors for 360 degree lighting estimation.

- Directional speakers near the ears for discrete, localized audio feedback

- Electrochromatic coatings on the reflectors for electrically controllable variable transparency

- Micro-actuators that move the displays by fractions of a millimeter to allow for variable and dynamic depth of field based on eye convergence

The field of view could be even further increased by moving to slightly non-ellipsoidal ‘freeform’ shapes for the reflector, or by slightly curving the displays themselves (like on many modern smartphones).

Mechanical tolerance is of the utmost importance, and without precise calibration, it’s hard to get everything to align. Expect a post about our efforts here as well as the optical specifications themselves next week.

However, on the whole, what you see here is an augmented reality system with two 120 fps, 1600×1440 displays with a field of view covering over a hundred degrees combined, coupled with hand tracking running at 150 fps over a 180°x 180° field of view. Putting this headset on, the resolution, latency, and field of view limitations of today’s systems melt away and you’re suddenly confronted with the question that lies at the heart of this endeavor:

What shall we build?

Update: The North Star headset is now open sourced! Learn more ›