For touch-based input technologies, triggering an action is a simple binary question. Touch the device to engage with it. Release it to disengage. Motion control offers a lot more nuance and power, but unlike with mouse clicks or screen taps, your hand doesn’t have the ability to disappear at will. Instead of designing interactions in black and white, we need to start thinking in shades of gray.

Let’s say there’s an app with two controls: left swipe and right swipe. When the user swipes right and naturally pulls the hand back to its original, the left swipe might get triggered accidentally. This is a false positive error, and bad UX. So, with hand data being tracked constantly, how do you stop hand interactions from colliding with one another?

1. Create cooldown periods

Let’s start with our earlier swiping example. To avoid registering a false positive, you can design your app to ignore subsequent swipes within a brief time window (one or two seconds) after the initial swipe. This gives the user time to return to the original position without accidentally triggering a second swipe.

2. Design explicit trigger actions

Actions that require more user intent than others will always be harder to trigger accidentally, and should be used when a false positive could disrupt the entire experience. One approach is to use clear switches in hand poses. In All the Cooks, for instance, switching from an open hand to pointing reveals additional menu options. Our internal testing has also found that bringing in two hands for an interaction is more explicit than a single one, and therefore harder to accidentally trigger.

3. Create a null mode

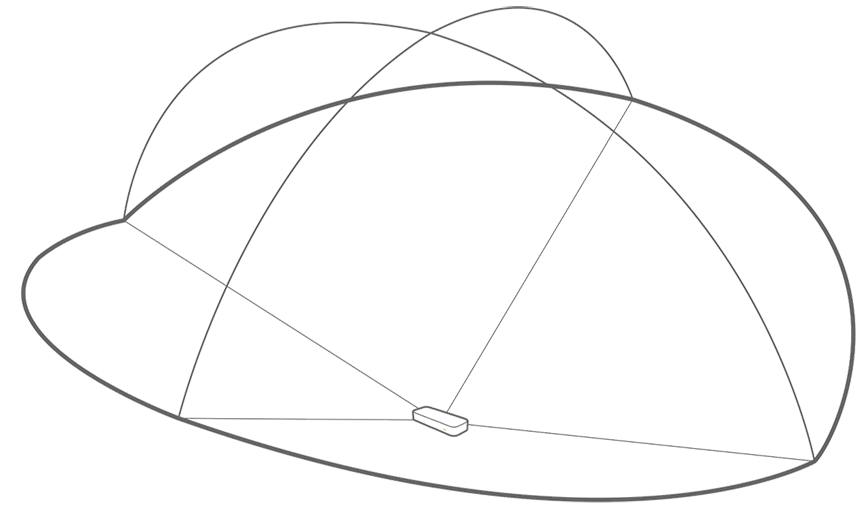

If tracking hand position is a key part of using your app, remember that users will want to completely stop tracking without having to remove their hand from the device’s field of view. Google Earth’s Leap Motion integration uses a variety of hand metrics – including pitch, yaw, and position – to let you soar above the globe. But since humans haven’t yet mastered the art of invisibility, pulling your open hand from the interaction space can send you into a tailspin. The solution? Making a fist stops your hand movements from impacting the app controls.

4. Use context-specific interactions

Any app experience can be imagined as a series of distinct contexts chained together by specific interactions. For each context, only a fraction of the app’s overall interaction set is likely to be relevant. If a part of your app has hand interactions that are often triggered accidentally, consider disabling irrelevant interactions in that context – like how Sculpting moves neighboring menu options out of the way so they’re not accidentally triggered when a radial menu opens.

5. Explore multi-modal input

As Daniel Widgor notes in Brave NUI World, have you ever noticed how the iPhone uses the touchscreen for application interactions, but physical buttons for external controls like on/off and volume? For more complex projects, you might want to consider multi-modal input that also uses voice or eye-tracking to determine user intent. In an insightful article on Smashing Magazine, Chris Noessel suggests using gestures for physical manipulations, while language can be used for abstractions. (By the way, if you’ve never read his blog on sci-fi interfaces, get ready to lose a weekend!)

6. Test and iterate

The best application design process is always iterative. Shake down the entire application flow, test out scenarios where the interactions might overlap, and find the pain points. Building with motion control means throwing out a lot of design principles that are built on legacy interaction models and exploring new ground. In testing and building on your app, always ask yourself: Where can Leap interaction make this experience better? And how can I make it easier for my users to achieve what they want?

Update 9/12/2014: Freeform has been redubbed Sculpting for V2.

Nice article Nancy, really enjoyed reading it. One more think to add will be understanding users intent to perform that action. What is the end goal and how easily can the user get to that interaction. Any interaction is more about the transition from one state to another. Smoother the transition better the interaction.

There is a good video I saw, which is not directly related to 3D inputs, but we can borrow some principles. The video is called the User is Drunk. Here is the link. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=r2CbbBLVaPk

I also like the point you made with multi modal inputs. 3D inputs lack robustness because human hand is not very steady. I have an example of using 3D input with keyboards for 3D modelling. you can use the hand as a cursor, but for having binary states you can use key presses from the keyboard. For example if you are doing scaling of an object, you can hold the S key and move your hand and it will scale the object. Once you release the key, it will stop registering the hand movements.

May 30, 2014 at 12:20 pmThanks, Sarang. Really good point about user intent. I’d love to see a future blog post about it to dive deeper into goal-oriented design.

Love the video, especially the beginning where he says that great UI is not there. That’s why I think technologies like the Leap brings us users closer to reaching our goals, so that we aren’t limited to using tools (mouse + keyboard) to use another tool (computer) to get there.

May 30, 2014 at 3:55 pm[…] a trail to guide a rolling ball through the level. This embraces the motion-tracking dilemma of the sensor always being on, and because of the game’s speed, the player doesn’t need to be extremely precise in order to […]

June 7, 2014 at 8:01 am[…] the sensor is always on, the Leap Motion Controller can track your hands anywhere within the total interaction space. With […]

June 22, 2014 at 8:17 am[…] The Sensor is Always On […]

September 21, 2015 at 9:00 am[…] we’ve discussed elsewhere, The Leap Motion Controller exhibits the “live-mic” or “Midas touch” problem. This means […]

February 24, 2016 at 6:50 am